Edward R. Murrow at the movies -- just when we need him most, some say

San Francisco Chronicle

Fri October 7, 2005

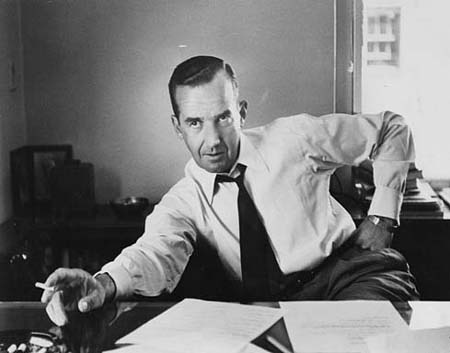

In 1958, CBS newsman Edward R Murrow admonished broadcasters to pursue serious new stories and use the airwaves to educate and inform, in spite of corporate and advertising pressures to entertain.

Murrow, easily America's most trusted pre-Cronkite anchorman, said television "is being used to distract, delude, amuse and insulate us," when he ardently believed it "can teach, it can illuminate ... it can even inspire. But it can do so only to the extent that humans are determined to use it to those ends. Otherwise it is merely wires and lights in a box."

In his feature-film homage to Murrow, "Good Night, and Good Luck," George Clooney quotes repeatedly from that "wires and lights" address to the Radio-Television News Directors Association. The black-and-white film was directed and co-written by Clooney and stars David Strathairn as Murrow. Shot cinema-verite style in a re-created 1950s newsroom, "Good Night, and Good Luck" -- its title was Murrow's signature sign-off -- is an account of Murrow's 1953 and "See It Now" broadcasts assailing Sen. Joseph McCarthy during the nation's anti-Communist hysteria.

"I'm the son of a journalist, and from the time I was very young my dad would recite that 'wires and lights' speech at our house," says Clooney (whose father, Nick, was a longtime Kentucky anchorman and admirer of Murrow) by phone from Los Angeles. "By the time I was a teenager, I was aware of two great high-water marks in American reporting: Murrow taking on McCarthy and Cronkite's report after coming back from Vietnam."

NPR's Daniel Schorr, 89, one of two surviving "Murrow boys," the talented cadre of young reporters hired by Murrow in the early days, says he appreciates Clooney's vision.

"It is wonderful to see Murrow brought back at his most effective moment, taking on McCarthy," Schorr said by phone. "The Murrow you see is exactly the Murrow I met in 1953. Maybe this is just the right time to reinvigorate his memory, since we're once again in a period when there is so much pressure against journalists doing their best."

"Good Night" doesn't scratch the surface of Murrow's personal life, and the 90-minute film doesn't waste time narrating the events that put Murrow directly in the path of McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee. Murrow had returned from the war a radio hero after reporting on the Blitz live from London's rooftops and entering Buchenwald as the first Allied correspondent inside the Nazi concentration camp. His wartime broadcasts brought an unprecedented immediacy to foreign news coverage and gripped listeners with his flinty courage and calm, resolute style. Back in the United States, he launched "See It Now," the first TV news magazine, and also concurrently hosted "Person to Person," the chatty, intimate template for all celebrity interview shows in its wake -- a legacy Murrow never lived down.

Murrow's moral idealism was tempered by an innate pessimism and discontent, and Strathairn plays him as a complicated, even reluctant, hero. A son of Quaker parents, raised in rural eastern Washington, where he worked as a young man in the lumber camps, Murrow prided himself on a lifelong populist streak that countered his patrician bearing. Clooney, who plays Murrow's producer Fred Friendly, thought about playing Murrow "for about 10 seconds, until I realized that Murrow was a man who always felt he had the weight of the world on his shoulders. That's not exactly something you think of when you think of me," he says with a laugh.

"I think (Clooney) didn't want the part because he didn't want to smoke," says Strathairn, a nonsmoker, with a sly smile, describing the two packs a day he had to puff to play the chain-smoking Murrow, who died of lung cancer in 1965.

Strathairn, 56, grew up in Marin County and was back in the Bay Area last week to promote the film. After a lengthy career playing mostly supporting roles ("L.A. Confidential," "Dolores Claiborne"), "Good Night" is Strathairn's first time anchoring a higher-profile project. "It definitely added a new level of fear, tackling such a legendary figure," says Strathairn, who took home the best actor award from the Venice Film Festival last month and has made an impressive battery of Oscar-hopeful lists. "Murrow had a very distinct presence, which you get from looking at all the photos and kinescopes, and I had the sense there was always a lot operating right under the surface," he says. Strathairn's performance captures that unsettled calm: Murrow's wary stare, a foot twitching nervously throughout broadcasts, a compulsive swig of scotch before going on air.

Murrow and McCarthy were at the peak of their powers when they faced off on TV. From the moment in a 1950 speech when McCarthy waved his infamous (and never-identified) "list of 205 Communists working in the State Department," the senator exploited the country's Cold War paranoia, relentlessly pursuing those he deemed Communist sympathizers. He also targeted Murrow, once the broadcaster began probing the senator's smear tactics.

Clooney made a canny decision to portray McCarthy with real archival footage. "If we had an actor play McCarthy, people would have said you're making him too arch," said Clooney, an unapologetic liberal, "so we thought, let's do just what Murrow did," and let McCarthy effectively indict himself in his own words. Clooney says that many people at test screenings asked the name of the actor playing McCarthy. "We want to take out ads in the trades saying, 'Joe McCarthy, for best supporting actor,' " he jokes.

"Good Night" arrives at a time Clooney knows is rife with discussion of the state of the news media, and whether TV news in particular too often chases ratings and profitability over substance. Clooney hopes "Good Night" reminds us of journalism at one of its finest hours, but also that the issue of entertainment pushing the news off the air is as old as television itself. "My father always argued that it is not just the right, but the duty, of the fourth estate to constantly question authority, or whoever is in charge," says Clooney. "Because without that scrutiny, we know authority corrupts. That's what we've learned over the course of our history, and it's what this movie is about -- the idea that it is our duty in a democracy to always ask questions."

Then Clooney again starts reciting from a Murrow speech, this time from the 1954 TV expose on McCarthy chronicled in "Good Night": "We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty." "We can't defend freedom abroad by deserting it at home."

Share your thoughts in the Forum

Share your thoughts in the Forum